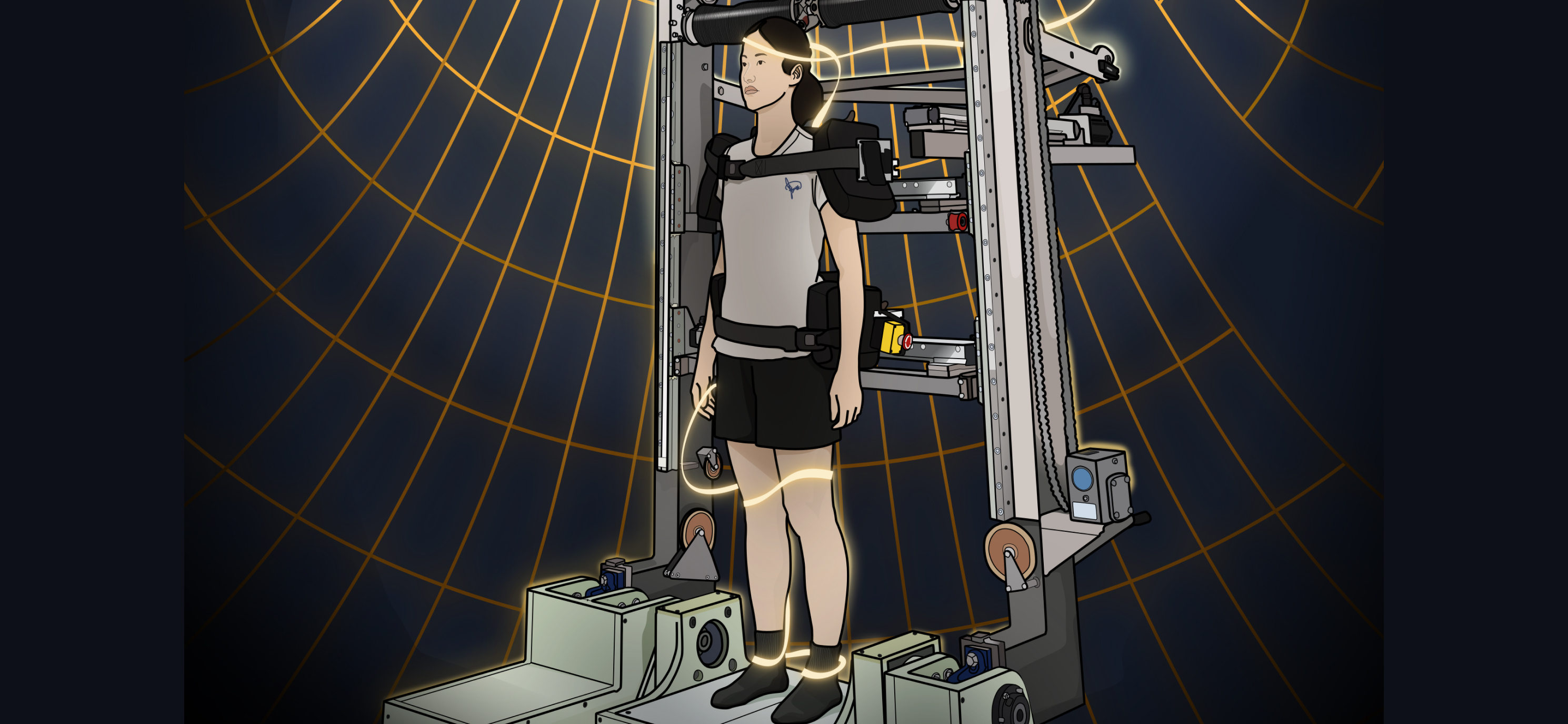

Acknowledgement: The illustration of the UBC balance robot was drawn by Julie Sugimoto

When you stand still, your brain is busy processing information that is already a few hundredths of seconds old. Those small delays - similar to the lag you experience when you watch a video that buffers - render your balance more difficult to maintain. These delays also increase for older adults or people with neurological conditions.

A research team from the University of British Columbia has engineered a balance robot that can virtualize your body, essentially allowing the researchers to dissociate your brain from your body. Using this novel tool, the team can alter the properties of your body so it feels heavier, lighter, more “sticky” or more “destabilising”, your muscles create motion in unusual directions (akin to a giving your brain a new body) and can even insert an artificial lag into the sensory signals that your brain uses to determine where your body is. By using this robotic tool, the researchers were able to assess, in real time, how the nervous system interprets and compensates for the lag, i.e. the information from the past it receives.

In a recent paper published in Science Robotics, an international team of researchers from the UBC School of Kinesiology, School of Biomedical Engineering, Balance and Falls Research Centre and Erasmus Medical Centre (NL) asked healthy volunteers to stand on their robotic balance platform. They changed two “spatial” features of the body:

- Inertia gain – how heavy your body feels (small values make you feel lighter; large values make you feel heavier).

- Viscosity gain – how much resistance you feel when you move (negative values inject energy in your motion, pushing your body further in the same direction of movement; positive values resist your movement – similar to a damper).

as well as a “temporal” feature of the body by inserting a lag between balance-correcting motor actions and their resulting whole-body movements.

When the robot added negative viscosity to the participant’s body, their sway grew and they crossed the limits of standing balance more often, essentially inducing virtual falls. This pattern was similar to when participants balanced on the robot with a 200 ms sensorimotor lag inserted between their motor commands and resulting motion, where all individuals fell.

Next, the researchers asked participants to sense their balance under spatial and temporal body alterations virtualized by the robot. Participants instinctively chose a “lighter body” and a destabilizing “negative viscosity” setting as perceptually equivalent to the feeling of balancing with a temporal lag. Intriguingly, participants chose a virtual body that was “heavier” and “dampened” to replicate their natural sense of balance when a 200 ms delay was present, effectively cancelling their perception of instability associated with this lag.

To test whether the perceptions reported by participants could actually compensate the destabilizing effects of time delays for the control of balance, ten naive volunteers stood on the robot with the lagand “heavier” or “dampened” versions of their body. Remarkably, their balance instantly improved - no training required - and only one participant experienced a virtual fall.

Why this novel research matters

For the sense and control of balance, the results from these experiments show that the brain processes information regarding the spatial properties of the body similarly to the temporal aspects of body movements. Instead of strictly differentiating spatial or temporal information, the authors proposed that the nervous system maintains probabilistic maps between balance motor actions and associated multisensory feedback. These maps appear to be largely indifferent to the precise spatial and temporal properties of the body and exhibit flexibly to the sensory consequences of our changing body. The authors further proposed that any updates to these maps will exhibit some overlap, enabling the neural structures responsible for standing balance to potentially benefit from specific combinations of space and time characteristics of the body. Thus, opening the door for applications enabling a future without falls!

Beyond the lab

- Robotics: Most bipedal robots keep space and time separate in their control algorithms. The current findings suggest a single, higher‑order controller that blends space and time could prove useful to give robots more human‑like, robust balance.

- Clinical outlook: Age‑related changes, diabetic neuropathy, multiple sclerosis and Friedreich’s ataxia can add neural delays that may contribute to falls. The current robotic advancements pave the way for the development of wearable or assistive devices to help at‑risk people stay upright.

The robot was engineered, built and validated in the UBC School of Kinesiology, Faculty of Education, with funding from NSERC (Research Tools & Instruments and Discovery Grants) and the UBC School of Kinesiology Equipment and Research Accelerator Fund.

In short, by turning people into “virtual avatars” with a novel robotic device, the researchers have uncovered a hidden, adaptable representation of space-time inside our brains - one that could soon be harnessed to make both robots and humans steadier on their feet.